Gynaecologist | Orthopaedic doctor

Dr. Himanshu Popli

DR.HIMANSHU POPLI specialised in diagnosing orthopaedic issues with the best technology available and the most advanced methods of treatments used for reliable and effective results. Moreover, he is also focused & passionate about sports trauma, replacement and arthroscopic surgeries.

Make an Appointment

+918755704819

Online Schedule

Book here

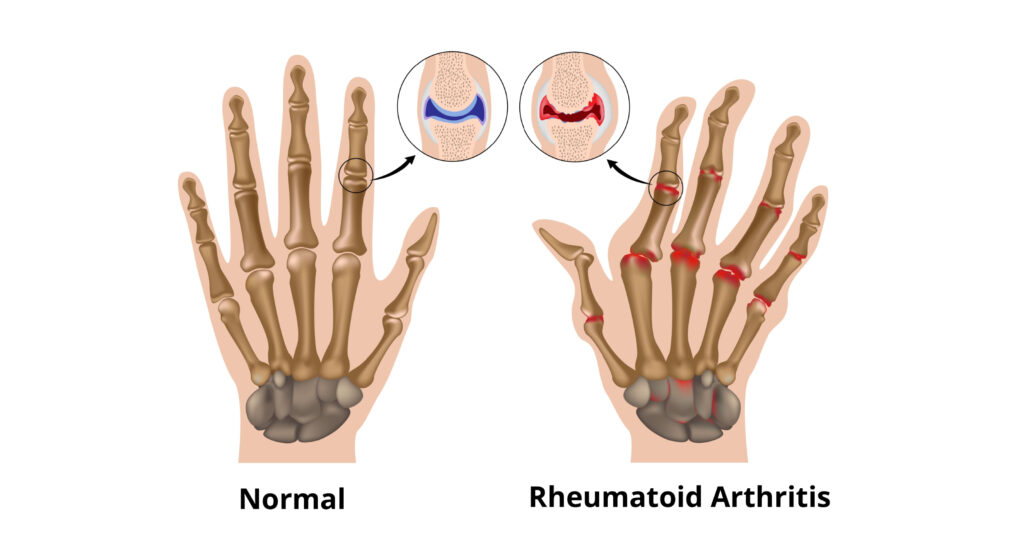

Rheumatoid Arthritis

What is Rheumatoid Arthritis ?

What causes rheumatoid arthritis?

What are the results of joint inflammation?

Ultimately, uncontrolled inflammation leads to joint deformities due to the destruction and wearing down of the cartilage, which normally acts as a “shock absorber” in-between joints.

Eventually, the bone itself erodes, potentially leading to fusion of the joint, which represents an effort of the body to protect itself from constant irritation from excessive inflammation.

This process is mediated by specific cells and substances of the immune system, which are produced locally in the joints but also circulate in the body, causing systemic symptoms.

What are the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis?

Rheumatoid arthritis affects each individual differently. In most people, joint symptoms may develop gradually over several years. In other people, rheumatoid arthritis may progress rapidly.

A few people may have rheumatoid arthritis for a limited period of time and then enter remission (a time with no symptoms).

How is rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed?

RA can be hard to detect because it may begin with subtle symptoms, such as achy joints or a little stiffness in the morning. Also, many diseases behave like RA early on.

Diagnosis of RA depends on the symptoms and results of a physical exam, such as warmth, swelling and pain in the joints.

Some blood tests also can help confirm RA. Telltale signs include:

Anaemia (a low red blood cell count)

Rheumatoid factor (an antibody, or blood protein, found in about 80 per cent of patients with RA in time, but in as few as 30 per cent at the start of arthritis)

Antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides (pieces of proteins), or anti-CCP for short (found in 60–70 per cent of patients with RA)

Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (a blood test that, in most patients with RA, confirms the amount of inflammation in the joints)

X-rays can help in detecting RA but may not show anything abnormal in early arthritis. Even so, these first X-rays may be useful later to show if the disease is progressing. Often, MRI and ultrasound scanning are done to help judge the severity of RA.

There is no single test that confirms an RA diagnosis for most patients with this disease. (This is above all true for patients who have had symptoms fewer than six months.) Rather, a doctor makes the diagnosis by looking at the symptoms and results from the physical exam, lab tests and X-rays.

How is rheumatoid arthritis treated?

The goals of rheumatoid arthritis treatment are as follows:

To control a patient’s signs and symptoms

To prevent joint damage

To maintain the patient’s quality of life and ability to function

Joint damage generally occurs within the first two years of diagnosis, so it is important to early diagnose and treat RA in the so-called “window of opportunity” to prevent long term consequences.

Non-pharmacologic therapies

Nonpharmacologic therapies include treatments other than medications and are the foundation of treatment for all people with rheumatoid arthritis.

Rest

When joints are inflamed, the risk of injury of the joint itself and the adjacent soft tissue structures (such as tendons and ligaments) is high. This is why inflamed joints should be rested.

However, physical fitness should be maintained as much as possible. At the same time, maintaining a good range of motion in your joints and good fitness overall is important in coping with the systemic features of the disease.

Exercise :

Pain and stiffness often prompt people with rheumatoid arthritis to become inactive. However, inactivity can lead to a loss of joint motion, contractions, and a loss of muscle strength. These, in turn, decrease joint stability and further increase fatigue.

Regular exercise, especially in a controlled fashion with the help of physical therapists and occupational therapists, can help prevent and reverse these effects. Types of exercises that have been shown to be beneficial include range of motion exercises to preserve and restore joint motion exercises to increase strength and exercises to increase endurance (walking, swimming, and cycling).

Physical and occupational therapy

Physical and occupational therapy can relieve pain, reduce inflammation, and help preserve joint structure and function for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Occupational therapists also focus on helping people with rheumatoid arthritis to be able to continue to actively participate in work and recreational activity with special attention to maintaining the good function of the hands and arms.

Nutrition and dietary therapy

Weight loss may be recommended for overweight and obese people to reduce stress on inflamed joints.

People with rheumatoid arthritis have a higher risk of developing coronary artery disease. High blood cholesterol is one risk factor for a coronary disease that can respond to changes in diet.

A nutritionist can recommend specific foods to eat or avoid in order to achieve a desirable cholesterol level.

Changes in diet have been investigated as treatments for rheumatoid arthritis, but there is no diet that is proven to cure rheumatoid arthritis.

No herbal or nutritional supplements, such as cartilage or collagen, can cure rheumatoid arthritis. These treatments can be dangerous and are not usually recommended.

Smoking and alcohol

Smoking is a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis, and it has been shown that quitting smoking can improve the condition. People who smoke need to quit completely.

Moderate alcohol consumption is not harmful to rheumatoid arthritis, although it may increase the risk of liver damage from some drugs such as methotrexate.

Measures to reduce bone loss

Inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis can cause bone loss, which can lead to osteoporosis. The use of prednisone further increases the risk of bone loss, especially in postmenopausal women. It is important to do a risk assessment and address risk factors that can be changed in order to help prevent bone loss. Patients may do the following to help minimize the bone loss associated with steroid therapy:

Therapy for RA has improved greatly in the past 30 years. Current treatments give most patients good or excellent relief of symptoms and let them keep functioning at, or near, normal levels. With the right medications, many patients can achieve “remission” — that is, they have no signs of active disease.

There is no cure for RA. The goal of treatment is to lessen your symptoms and poor function.

Doctors do this by starting proper medical therapy as soon as possible before your joints have lasting damage.

No single treatment works for all patients. Many people with RA must change their treatment at least once during their lifetime.

Good control of RA requires early diagnosis and, at times, aggressive treatment.

Thus, patients with a diagnosis of RA should begin their treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs — referred to as DMARDs. These drugs relieve not only symptoms but also slow the progression of the disease.

Often, doctors prescribe DMARDs along with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDs and/or low-dose corticosteroids to lower swelling, pain and fever.

DMARDs have greatly improved the symptoms, function and quality of life for nearly all patients with RA. Common DMARDs include methotrexate, leflunomide (Arava), hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine.

An improvement in symptoms may require four to six weeks of treatment with methotrexate. Improvement may require one to two months of treatment with sulfasalazine and two to three months of treatment with hydroxychloroquine.

Patients with more serious disease may need medications called biologic response modifiers or “biologic agents.” Usually, they are reserved for patients who do not adequately respond to DMARDs or if adverse prognostic factors

Are present. They can target the parts of the immune system and the signals that lead to inflammation and joint and tissue damage. FDA-approved drugs of this type include abatacept (Orencia), adalimumab (Humira), anakinra, certolizumab (Cimzia), etanercept (Enbrel), golimumab (Simponi), infliximab (Remicade), rituximab and tocilizumab (Actemra). Most often, patients take these drugs with methotrexate, as the mix of medicines is more helpful.

DMARDs and biological agents interfere with the immune system’s ability to fight infection and should not be used in people with serious infections.

Testing for tuberculosis (TB) is needed before starting DMARD and anti-TNF therapy.

People who have evidence of prior TB infection should be treated for TB because there is an increased risk of developing active TB while receiving anti-TNF therapy.

AntiTNF agents are not recommended for people who have lymphoma or who have been treated for lymphoma in the past. People with rheumatoid arthritis, specially those with severe disease, have an increased risk of lymphoma regardless of what treatment is used.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are another type of DMARD. People who cannot be treated with methotrexate alone may be prescribed a JAK inhibitor such as tofacitinib (Xeljanz). And olumiant

The best treatment of RA needs more than medicines alone.

You will need frequent visits throughout the year with your rheumatologist. These checkups let your doctor track the course of your disease and check for any side effects of your medications.

You likely also will need to repeat blood tests and X-rays or ultrasounds from time to time.

Surgery

When bone damage from arthritis has become severe, or pain is not controlled with medications, surgery is an option to restore function to a damaged joint.

Living with rheumatoid arthritis

Research shows that people with RA, mainly those whose disease is not well controlled, have a higher risk for heart disease and stroke. Talk with your doctor about these risks and ways to lower them.

It is important to be physically active most of the time but to sometimes scale back activities when the disease flares.

In general, rest is helpful when a joint is inflamed or when you feel tired. At these times, do gentle range-of-motion exercises, such as stretching. This will keep the joint flexible.

When you feel better, do low-impact aerobic exercises, such as walking, and exercises to boost muscle strength. This will improve your overall health and reduce pressure on your joints.

A physical or occupational therapist can help you find which types of activities are best for you and at what level or pace you should do them.

Finding that you have a chronic illness is a life-changing event. It can cause worry and sometimes feelings of isolation or depression. Use the lowest possible dose of glucocorticoids for the shortest possible time, when possible, to minimize bone loss.

Consume an adequate amount of calcium and vitamin D, either in the diet or by taking supplements.

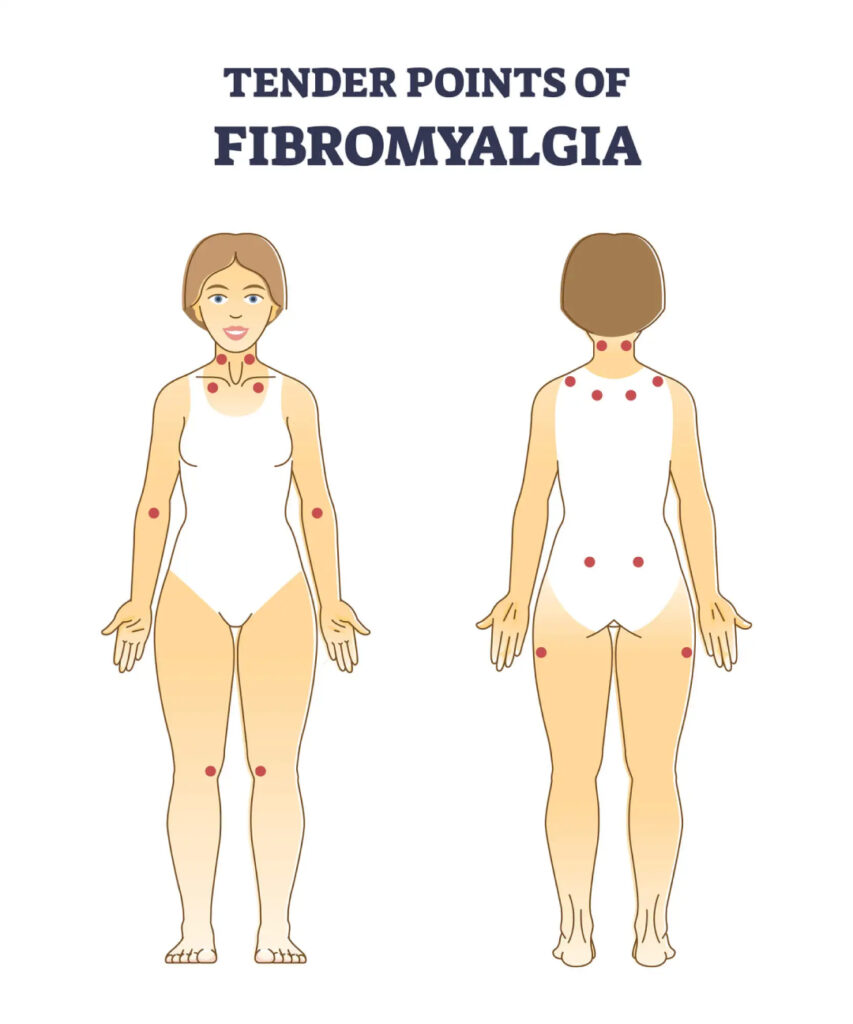

Fibromyalgia

What is Fibromyalgia?

Fibromyalgia is a chronic medical condition characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, along with other symptoms like fatigue, sleep disturbances, and cognitive difficulties often referred to as “fibro fog.” It is a complex and poorly understood disorder, and its exact cause is not known. Fibromyalgia is considered a central sensitivity syndrome, which means that the central nervous system appears to be hypersensitive, amplifying painful sensations.

Here are some key features and symptoms of fibromyalgia:

1. Widespread Pain: The hallmark symptom of fibromyalgia is a widespread, chronic pain that typically affects both sides of the body. The pain is often described as a constant dull ache and may vary in intensity.

2. Tender Points: Fibromyalgia is often diagnosed based on the presence of tender or trigger points in specific areas of the body. These tender points are localized areas that are exceptionally sensitive to pressure.

3. Fatigue: People with fibromyalgia frequently experience profound fatigue, even after a full night’s sleep. This fatigue can be debilitating and is often accompanied by a lack of energy and stamina.

4. Sleep Disturbances: Fibromyalgia is associated with sleep problems, including difficulties falling asleep and staying asleep. People with fibromyalgia often wake up feeling unrefreshed.

5. Cognitive Symptoms: Many individuals with fibromyalgia report cognitive difficulties, such as memory problems, difficulty concentrating, and a feeling of mental fogginess, which is sometimes called “fibro fog.”

6. Other Symptoms: Fibromyalgia can be associated with a variety of other symptoms, including headaches, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), restless legs syndrome, and sensitivity to temperature changes.

The exact cause of fibromyalgia is not known, but it is believed to be a combination of genetic, environmental, and neurobiological factors. Stress, physical trauma, and infections have been suggested as potential triggers.

Diagnosing fibromyalgia can be challenging because there are no specific laboratory tests or imaging studies that can confirm it. Diagnosis is typically made based on clinical criteria, including the presence of widespread pain and the identification of tender points. It’s important to rule out other conditions with similar symptoms through medical evaluation.

Management of fibromyalgia

often involves a combination of treatments, including medication (such as pain relievers, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants), physical therapy, exercise, and lifestyle changes to improve sleep and reduce stress. The goal is to help manage the symptoms and improve the patient’s quality of life, as there is no cure for fibromyalgia. Additionally, a multidisciplinary approach that includes education and support is often beneficial for individuals living with fibromyalgia.

The exact cause of fibromyalgia is not fully understood, and it is believed to be a complex interplay of various factors. While the precise cause remains elusive, several factors have been suggested to contribute to the development of fibromyalgia:

1. Genetic Predisposition: There appears to be a genetic component to fibromyalgia, as it tends to run in families. Certain genetic markers may increase a person’s susceptibility to the condition.

2. Abnormal Pain Processing: One prevailing theory is that individuals with fibromyalgia have an altered perception of pain. The central nervous system, including the brain and spinal cord, may become hypersensitive to pain signals, amplifying the perception of pain.

3. Physical or Emotional Trauma: A significant physical trauma, such as a car accident or surgery, or emotional trauma, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), has been associated with the onset of fibromyalgia in some cases. These events may trigger or exacerbate symptoms.

4. Infections: In some cases, infections or illnesses, such as the Epstein-Barr virus or Lyme disease, have been linked to the development of fibromyalgia. It is believed that the body’s response to these infections may play a role.

5. Abnormal Brain Chemistry: Some research suggests that imbalances in certain neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain) may contribute to the development of fibromyalgia. These imbalances can affect mood, sleep, and pain perception.

6. Hormonal Factors: Hormonal changes, such as those that occur during menopause, may trigger or worsen fibromyalgia symptoms in some individuals. Estrogen, in particular, is thought to influence pain perception.

7. Immune System Abnormalities: Some studies have found abnormalities in the immune systems of people with fibromyalgia. It is hypothesized that these immune system disturbances may contribute to the condition.

8. Oxidative Stress: There is ongoing research into the role of oxidative stress (cellular damage caused by free radicals) in fibromyalgia, as it may be linked to pain and fatigue.

It’s important to note that fibromyalgia is a complex and multifactorial condition, and not all individuals with the condition will have the same contributing factors. Additionally, some people may develop fibromyalgia without any apparent triggering event.

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia is typically made based on clinical criteria, including the presence of widespread pain and tender points, and after ruling out other conditions with similar symptoms. While the exact cause remains a subject of ongoing research, treatment for fibromyalgia primarily focuses on symptom management and improving the patient’s quality of life. This often involves a combination of medication, physical therapy, exercise, and lifestyle adjustments.

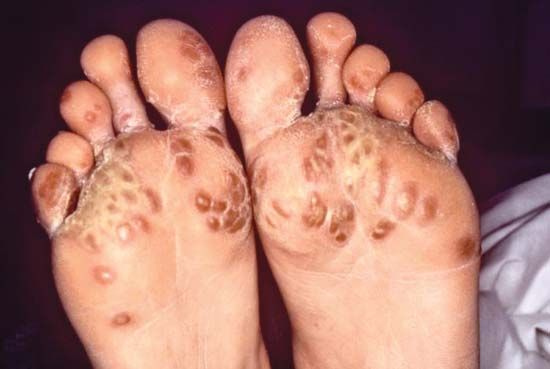

Reactive Arthritis

What is Reactive arthritis (ReA)?

Reactive arthritis is a noninfectious inflammation of one or several joints.

It may be self-limited, relapsing or chronic.

The condition sometimes follows an infection of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary system.

There may be other non-joint features such as eye, genital tract, bowel or skin inflammation.

Who gets reactive arthritis?

ReA may follow an infection of the genital tract or bowel, but this is not always identified.

It is more common in men and Caucasians. ReA is rare after the age of 50.

The disease is associated with the HLA B27 gene in 50 -80% of patients.

What causes reactive arthritis?

The cause of ReA is unknown.

It is associated with the HLA B27 gene, but it is unclear why. It is also unclear why ReA is sometimes associated with infection. (Bacterial infections of the genital tract with Chlamydia or gastrointestinal tract with Shigella, Salmonella, or Campylobacter).

What are the signs and symptoms of reactive arthritis?

ReA may follow several weeks after a genital tract or bowel infection. The patient may have acute swelling, pain and redness in one or more joints.

Typically, it is more common in the lower extremity joints.

During the joint symptoms, one may also have noninfectious genital tract, skin or eye inflammation.

ReA patients may have tendonitis, especially of the heel. There may be spine involvement (like ankylosing spondylitis).

Traditionally, ReA is self-limited to 3 to 12 months, but up to 50% may have a relapsing or chronic disease. The disease is not life-threatening, and most people are able to work and function normally.

How is reactive arthritis diagnosed?

The diagnosis is typically made by a doctor taking a thorough history and physical examination.

A swollen joint may be aspirated to rule out an infection or gout. There is no specific test for the diagnosis of ReA. The HLA B27 gene may be checked by blood test in selected cases, but it is not diagnostic.

How is reactive arthritis treated?

At this time, there is no curative treatment. Any existing infection, if discovered, should be treated. The role of routine antibiotics is controversial.

Physical therapy, stretching and exercise are prescribed.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are given for pain and stiffness.

Steroid injections to involved tendons or joints can help relieve pain and inflammation.

In chronic or relapsing cases, similar treatments to rheumatoid arthritis can be considered to include methotrexate, sulfasalazine and the biologic antiTNFa drugs.

Psoriasis

What is psoriasis?

Psoriasis is a chronic skin disorder that produces thick, pink to red, itchy areas of skin covered with white or silvery scales.

The rash usually occurs on the scalp, elbows, knees, lower back and genitals, but it can appear anywhere. It can also affect the fingernails.

Psoriasis usually begins in early adulthood, but it can start later in life. The rash can heal and come back throughout a person’s life.

Psoriasis is not contagious and does not spread from person to person. In most people, the rash is limited to a few patches of skin.

In severe cases, it can cover large areas of the body.

How does the rash start?

Psoriasis starts as small red bumps that grow in size, on top of which scale forms. These surface scales shed easily, but scales below them stick together.

When scratched, the lower scales may tear away from the skin, causing pinpoint bleeding. As the rash grows larger, “plaque” lesions can form.

What are the symptoms of psoriasis?

As well as the symptoms described above, the rash can be associated with:

Itching

Dry and cracked skin

Scaly scalp

Skin pain

Pitted, cracked, or crumbly nails

Joint pain

What are less common forms of psoriasis?

nverse psoriasis Psoriasis found in skin folds. This form may present as thin pink plaques without scale.

Guttate psoriasis Small, red, drop-shaped, scaly spots in children and young adults that often appear after a sore throat caused by a streptococcal infection.

Pustular psoriasis Small, pus-filled bumps appear on the usual red patches or plaques.

Sebopsoriasis Typically located on the face and scalp; this form is made of red bumps and plaques with a greasy yellow scale. This is an overlap between psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis.

How can I know if I have psoriasis?

If you have a skin rash that does not go away, contact your healthcare provider. He or she can look at the rash to see if it is psoriasis or another skin condition.

A small sample of skin may be taken to view under a microscope.

What causes psoriasis?

The cause of psoriasis is unknown. The condition tends to run in families, so it may be passed on to children by parents.

Psoriasis is related to a problem of new skin cells developing too quickly. Normally, skin cells are replaced every 28 to 30 days.

In psoriasis, new cells grow and move to the surface of the skin every three to four days. The build-up of old cells being replaced by new cells creates the hallmark silvery scales of psoriasis.

What causes psoriasis outbreaks?

No one knows what causes psoriasis outbreaks. How serious and how often outbreaks happen with each person. Outbreaks may be triggered by:

Skin injury (for example, cuts, scrapes or surgery)

Emotional stress

Cold, cloudy weather

Streptococcal and other infections

Certain prescription medicines (for example, lithium and certain beta

blockers)

How is psoriasis treated?

Your healthcare provider will select a treatment plan depending on the seriousness of the rash, where it is on your body, your age, health, and other factors.

For a limited disease affecting only a few areas on the skin, topical creams or ointments may be all that is needed. When larger areas are involved or joint pain indicating arthritis is suspected, additional therapy may be needed.

Common treatments include:

Steroid creams

Moisturizers (to relieve dry skin)

Anthralin (a medicine that slows skin cell production)

Coal tar (common for scalp psoriasis; may also be used with light therapy for severe cases; available in lotions, shampoos and bath solutions)

Vitamin D3 ointment

Vitamin A or “retinoid” creams. Vitamin A in foods and vitamin pills has no effect on psoriasis.

Treatment for severe cases:

Light therapy (ultraviolet light at specific wavelengths decreases inflammation in the skin and helps to slow the production of skin cells)

PUVA (treatment that combines a medicine called “psoralen” with exposure to a special form of ultraviolet light)

Methotrexate (a medicine taken by the mouth; methotrexate can cause liver disease, so its use is limited to severe cases and is carefully watched with blood tests and sometimes liver biopsies)

Retinoids (a special form of Vitamin A-related drugs, retinoids can cause serious side effects, including birth defects)

Cyclosporine (a very effective capsule reserved for severe psoriasis because it can cause high blood pressure and damage to kidneys).

Newer drugs for treating psoriasis include injectable immune “biologic” therapies as well as small molecule immune-modulating pills. They work by blocking the body’s immune system from “kickstarting” an autoimmune disease such as psoriasis. These include anti-TNF agents like Enbrel, Humira and secukinumab (cosentyx) and ustekinumab.

Can psoriasis be cured?

Psoriasis cannot be cured, but treatment greatly reduces symptoms, even in severe cases. Tips for improving psoriasis in addition to prescription medicines:

Use moisturizer.

Avoid using harsh soaps.

Apply oil or moisturizer after bathing.

Use tar or salicylic acid shampoo for scale on the scalp.

What is psoriatic arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of inflammatory arthritis.

Up to 30 per cent of people with psoriasis can develop psoriatic arthritis.

Both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are chronic autoimmune diseases – meaning conditions in which certain cells of the body attack other cells and tissues of the body.

Psoriasis is most commonly seen as raised red patches or skin lesions covered with a silvery white build-up of dead skin cells, called a scale.

Scales can occur on any part of the body. Psoriasis is not contagious – you cannot get psoriasis from being near someone with this condition or from touching psoriatic scales.

There are five different types of psoriatic arthritis. The types differ by the joints involved, ranging from only affecting the hands or spine areas to a severe deforming type called arthritis mutilans.

Like psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis symptoms flare and subside, vary from person to person, and even change locations in the same person over time.

How is psoriatic arthritis diagnosed?

There is no single test to diagnose psoriatic arthritis. Doctors make the diagnosis based on a patient’s medical history, physical exam, blood tests, laboratory tests and MRIs and/or Xrays of the affected joints.

X-rays are not usually helpful in making a diagnosis in the early stages of the disease.

In the later stages, X-rays may show changes that are more commonly seen only in psoriatic arthritis.

The diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis is easier for your doctor to confirm if psoriasis exists along with symptoms of arthritis.

However, in as many as 15% of patients, symptoms of psoriatic arthritis appear before symptoms of psoriasis.

Since the disease symptoms can vary from patient to patient, it is even more important to meet with your doctor when symptoms worsen, or new symptoms appear.

What are the symptoms of psoriatic arthritis?

The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis may be gradual and subtle in some patients; in others, they may be sudden and dramatic.

The most common symptoms – and you may not have all of these of psoriatic arthritis are:

Discomfort, stiffness, pain, throbbing, swelling, or tenderness in one or more joints

Reduced range of motion in joints

Joint stiffness and fatigue in the morning

Tenderness, pain, or swelling where tendons and ligaments attach to the bone (enthesitis); example: Achilles’Achilles’ tendonitis

Inflammation of the eye (such as iritis)

Silver or grey scaly spots on the scalp, elbows, knees, and/or the lower spine

Inflammation or stiffness in the lower back, wrists, knees or ankles

Swelling in the distal joints (small joints in the fingers and toes closest to the nail), giving these joints a sausage-like appearance

Pitting (small depressions) of the nails Detachment or lifting of fingernails or toenails

Other tests supportive for the diagnosis

Positive testing for elevated sedimentation rate (indicates the presence of inflammation)

Positive testing for elevated C reactive protein (indicates the presence of acute inflammation)

A negative test for rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP( performed to rule out rheumatoid arthritis)

Anaemia a state in which there is a decrease in haemoglobin

Who is at risk for psoriatic arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis occurs most commonly in adults between the ages of 30 and 50; however, it can develop at any age.

Psoriatic arthritis affects men and women equally.

Up to 40% of people with psoriatic arthritis have a family history of skin or joint disease.

Children of parents with psoriasis are three times more likely to have psoriasis and are at greater risk for developing psoriatic arthritis than children born of parents without psoriasis.

If you do have psoriasis, let your doctor know if you are having joint pain. In as many as 85% of cases, skin disease occurs before the joint disease.

What causes psoriatic arthritis?

The cause of psoriatic arthritis is unknown. Researchers suspect that it develops from a combination of genetic (heredity) and environmental factors.

They also think that immune system problems, infection, and physical trauma play a role in determining who will develop the disorder.

Psoriasis itself is not an infectious condition.

Recent research has shown that people with psoriatic arthritis have an increased level of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) in their joints and affected skin areas. These increased levels can overwhelm the immune system, making it unable to control the inflammation associated with psoriatic arthritis.

The approach to treatment

Early diagnosis and treatment can relieve pain and inflammation and help prevent progressive joint involvement and damage.

Without treatment, psoriatic arthritis can potentially be disabling and crippling.

The type of treatment will depend on how severe your symptoms are at the time of diagnosis. Some early indicators of more severe disease include onset at a young age, multiple joint involvement, and spinal involvement.

Good control of the skin may be valuable in the management of psoriatic arthritis.

In many cases, you may be seen by two different types of doctors – a rheumatologist and a dermatologist.

What are the treatment options for psoriatic arthritis?

The aim of treatment for psoriatic arthritis is to relieve symptoms. Treatment may include any combination of the following:

Choice of medications depends on disease severity, the number of joints involved, and associated skin symptoms.

During the early stages of the disease, mild inflammation may respond to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Cortisone injections may be used to treat ongoing inflammation in a single joint.

However, oral steroids, if used to treat psoriatic arthritis, can worsen the skin rash due to psoriasis worse.

DMARDs are used when NSAIDs fail to work and in patients with erosive disease.

DMARDs that are effective in treating psoriatic arthritis include methotrexate, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, leflunomide and biologic agents. Sometimes combinations of these drugs may be used together.

The anti-malarial drug usually is avoided as it can cause a flare of psoriasis. Azathioprine may help those with severe forms of psoriatic arthritis.

The biologic agents are among the most exciting drug treatments. Both DMARDS and Biologics not only do these drugs reduce the signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis, but they also slow down joint damage.

Enbrel (etanercept)

Humira (adalimumab)

Remicade (inflixamab)

Simponi (golimumab)

Stelara (ustekinumab)

Secukinumab(cosentyx)

Newer agents like tofacitinib also reduce psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Other non-medicine therapies

Exercise: Moderate, regular exercise may relieve joint stiffness and pain caused by the swelling seen with psoriatic arthritis. Range of motion and strengthening exercises specifically for you combined with low impact aerobics may be helpful.

Improper exercise programs may make psoriatic arthritis worse. Before beginning any new exercise program, discuss exercise options with a doctor.

Heat and cold therapy

Heat and cold therapy involve switching the use of moist heat and cold therapy on affected joints. Moist heat supplied by a warm towel, hot pack, or warm bath or shower helps relax aching muscles and relieve joint pain, swelling, and soreness. Cold therapy supplied by a bag of ice can reduce swelling and relieve pain by numbing the affected joints.

Joint protection and energy conservation

Daily activities should be performed in ways that reduce excess stress and fatigue on joints. Proper body mechanics (the way you position your body during a physical task) may protect not only joints but also conserve energy. People with psoriatic arthritis are encouraged to frequently change body position at work, at home, and during leisure activities. Maintaining good posture standing up straight, and not arching your back is helpful for preserving function.

Does surgery have a role?

Surgery: Most people with psoriatic arthritis will never need surgery. However, severely damaged joints may require joint replacement surgery

The goal of surgery is to restore function, relieve pain, improve movement, or improve the physical appearance of the affected area.

Broader health impact of psoriatic arthritis

The impact of psoriatic arthritis depends on the joints involved and the severity of symptoms. Fatigue and anaemia are common.

Some psoriatic arthritis patients also experience mood changes. Treating arthritis and reducing the levels of inflammation helps with these problems.

People with psoriasis are slightly more likely to develop high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity or diabetes.

Maintaining a healthy weight and treating high blood pressure and cholesterol are also important aspects of treatment. There is no cure for psoriatic arthritis.

Once you understand the disease and learn to predict the ways in which your body responds to the disease, you can use exercise and therapy to alleviate discomfort and reduce stress and fatigue.

Mental exercises, as well as sharing your experiences with family, a counsellor, or a support group, may help you cope with the emotional stress related to changes in physical appearance and disability associated with the disorder

Gout

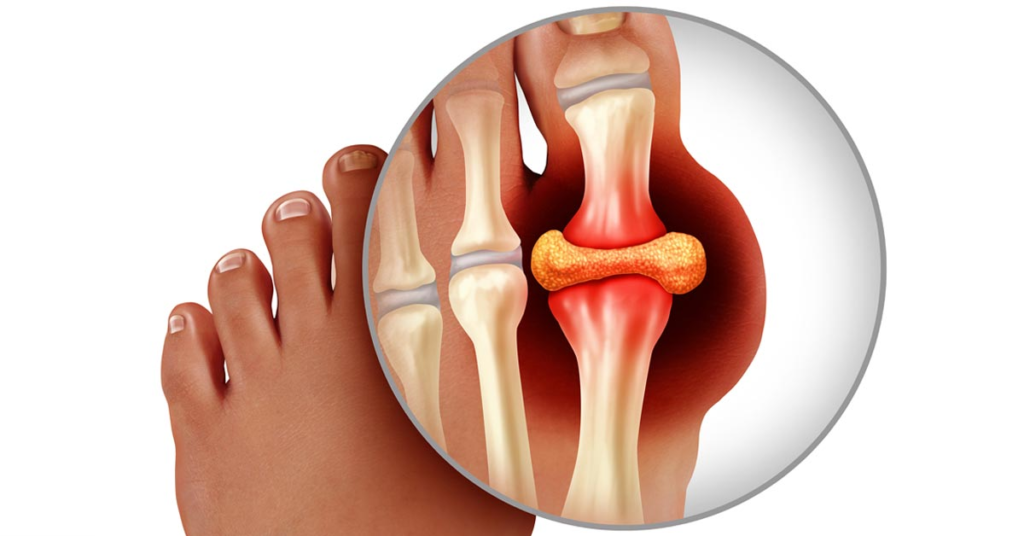

What is gout?

A gout is a form of arthritis that causes sudden, severe attacks of pain, tenderness, redness, warmth, and swelling (inflammation) in some joints.

It often affects one joint at a time but may affect a few or even many.

The large toe is most often affected, but gout can also affect other joints in the leg (knee, ankle, foot) and less often in the arms (hand, wrist, and elbow). The spine is rarely affected.

What are the symptoms of gout?

Sudden, intense joint pain, which often first occurs in the early morning hours

A swollen, tender joint that’s warm to the touch

Red or purple skin around the joint

What causes gout?

Although diet and excessive drinking of alcohol can contribute to the development of gout, they are not the main cause of the disorder.

Gout results from abnormal deposits of sodium urate crystals around the joint cartilage and their later release into the joint fluid.

Urate crystals can also form in the kidney, causing kidney stones.

Sodium urate is formed from uric acid, a natural chemical in the body.

Uric acid comes from the natural breakdown of RNA and DNA (the genetic material in cells). Some foods contain large amounts of uric acid, especially red meats and internal organs (such as liver and kidneys), some shellfish, and anchovies.

Patients who eat more meat and fish (and less dairy) or drink more beer and liquor seem to be more prone to gout.

But changing these habits may only partially reduce the likelihood of stopping gout attacks once they have started.

Uric acid in low amounts remains dissolved in the blood, passes through the kidneys and gastrointestinal system, and leaves the body as waste.

Uric acid in high amounts (higher than 6.7 mg/dL) will settle out of the blood and deposit in joints and make a person more likely to develop gout.

The amount of uric acid in your blood can change depending on

How efficiently your kidney gets rid of the uric acid in the blood (the main cause of elevated levels)

- Your weight

- What you eat

- Your overall health

- How much alcohol you drink

- What medicines you are taking

- Sudden illnesses

Not everyone with high levels of uric acid will develop gout. The Kidney’s ability to rid the body of uric acid is partly determined by heredity.

Yet, just because someone in the family has gout does not mean everyone in that family will have the disorder.

Often, the effect of heredity is modified by the risk factors mentioned above that affect uric acid, as well as male sex and age. All of these factors increase the risk of gout.

How frequent are gout attacks?

Gout attacks can recur from time to time in the same or different joints.

The initial attack may last several days to two weeks unless it is treated.

Over time, gout attacks may occur more often, involve more joints, have more severe symptoms, and last longer. Repeated attacks can damage the joint.

Lumpy collections of uric acid called tophi can develop near joints, in the skin, or within bones.

Some people will only have a single attack. However, about 90 per cent of patients who have one gout attack will have at least a second attack, although it may not occur for several years after the initial attack. Others may have attacks every few weeks.

Who is affected by gout?

Men (usually over age 40) and women after menopause

People who are overweight

People who frequently drink alcohol

When gout affects women, it is usually after menopause, especially in women who are taking certain medicines.

Younger patients may be affected by gout if they have been taking certain medicines for long periods of time, frequently drink alcoholic beverages, or have certain genetic disorders.

How is gout diagnosed?

Gout cannot be diagnosed simply from a blood test since many people have elevated blood uric acid levels but never develop gout. Rather, gout is diagnosed from the fluid withdrawn from an inflamed joint.

The fluid is observed under a microscope for sodium urate crystals.

Fluid is removed through a needle from the inflamed joint during a procedure called arthrocentesis.

Removing the fluid may reduce pressure within the joint and thereby reduce pain.

A lack of crystals does not necessarily rule out a diagnosis of gout. Occasionally, crystals may not be observed the first time but maybe seen if additional fluid is removed at another time during a subsequent attack.

Since gout can cause chronic joint pain and involve other joints, it is extremely important that an accurate diagnosis be made. Then, your doctor can prescribe the appropriate specific treatment.

How is gout treated?

There is no cure for gout, but it can be treated and controlled. Symptoms are often dramatically improved within 24 hours after treatment has begun.

Attacks can be prevented with appropriate therapy to lower the blood uric acid level.

The goals of treatment are to:

Relieve pain and inflammation

Prevent future gout attacks that could lead to permanent joint damage

The type of treatment prescribed will depend on several factors, including the person’s age, type of medicines he or she is taking, overall health, medical history, and severity of gout attacks.

Gout is mainly treated with medicine.

NSAIDs usually reduce inflammation and pain within hours.

Anti-inflammatory drugs will reduce the pain and swelling of attacks. They are usually continued until the gout attack completely resolves.

Corticosteroids may be prescribed for people who cannot take NSAIDs. Steroids also work by decreasing inflammation. Steroids can be injected into the affected joint or given as pills.

Colchicine is sometimes used in low doses for a long period of time to reduce the risk of recurrent attacks of gout.

If side effects from the therapy occur, treatment may be changed to a different medication. Your health care provider will discuss the potential side effects with you.

If you have kidney disease, heart failure, diabetes, ulcer disease or other chronic conditions, the choice of therapy to treat the gout is affected.

Drugs that lower the level of uric acid in the blood. (Examples are allopurinol, probenecid and febuxostat).

These drugs are recommended for patients who have had multiple attacks of gout or kidney stones due to uric acid.

The goal of treatment is to reduce the uric acid level to less than 6 mg/dL.

The goal of lowering the blood uric acid is to slowly dissolve joint deposits of sodium urate. Lowering the uric acid will not treat an acute attack but will, over time, prevent additional attacks from occurring. A sudden lowering of the uric acid level may cause an acute attack of gout.

To prevent acute attacks in people who are taking uric acid lowering drugs, colchicine or an NSAID is temporarily prescribed. If an attack occurs while taking a medication to lower the uric acid, this medicine should NOT be stopped; stopping and starting the uric acid lowering medication may cause additional attacks.

Not all patients will develop side effects from gout medications. How often any side effect occurs varies from patient to patient. The occurrence of side effects depends on the dose, type of medication, concurrent illnesses, or other medicines the patient may be taking.

If any rash or itching develops while taking allopurinol, the medicine should be stopped immediately, and your physician notified.

Can gout be treated through diet?

Dietary changes for most people do not play a major role in controlling their uric acid levels.

However, limiting certain foods, such as fructose-containing corn syrup, that cause increased production of uric acid and reducing alcohol intake is often helpful

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing Spondylitis( Seronegative Spondyloarthritis)

Spondyloarthritis

It is a type of arthritis that attacks the spine and, in some people, the joints of the arms and legs.

It can also involve the skin, intestines and eyes. The main symptom (what you feel) in most patients is low back pain. This occurs most often in axial spondyloarthritis.

In a minority of patients, the major symptom is pain and swelling in the arms and legs. This type is known as peripheral spondyloarthritis.

Many people with axial spondyloarthritis progress to having some degree of spinal fusion, known as ankylosing spondylitis.

Diseases & Conditions

Ankylosing spondylitis

Psoriatic arthritis

Reactive arthritis/Reiter’s syndrome

Enteropathic arthritis

Undifferentiated: Patients with features of more than one disease who do not fit in the defined categories above

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS)

AS is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disease of the joints and ligaments of the spine. Other joints may be involved.

This typically results in pain and stiffness in the spine.

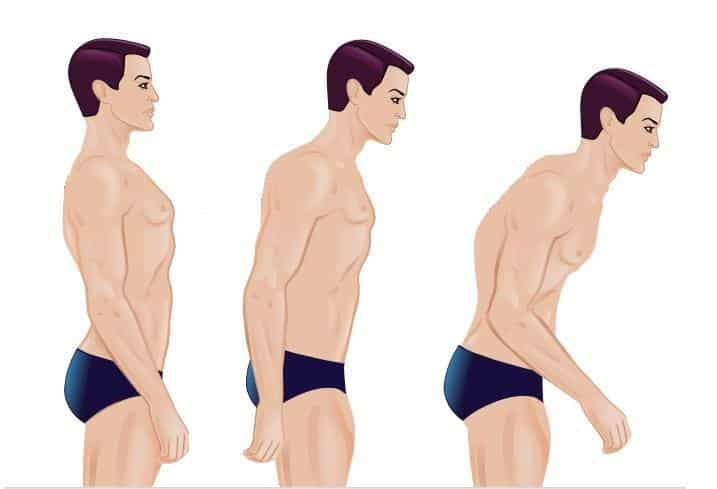

The disease may be mild to severe. The bones of the spine may fuse over time, causing a rigid spine.

Early diagnosis and treatment may help control the symptoms and reduce debility and deformity.

Who gets ankylosing spondylitis (AS)?

The onset is typically in late adolescence to early adulthood. It is rare for AS to begin after age 45. Ankylosing spondylitis tends to start in the teens and 20s and strikes males two to three times more often than females.

Family members of affected people are at higher risk, depending partly on whether they inherited the HLA-B27 gene.

The incidence is 1 in 1000 persons. About 90% of people with AS have the HLA B27 gene.

What causes ankylosing spondylitis (AS)?

The cause of AS is unknown, although there appears to be some genetic component. AS is associated with the HLA B27 gene, but it is unclear why. The gene is seen in about 8% of normal Caucasians. There are no known infectious or environmental causes. The gut organisms may play a role in causing the disease.

What are the signs and symptoms?

Early on, there is pain and stiffness in the buttocks and low back due to sacroiliac joint involvement.

Over time, the symptoms can progress up the spine to involve the low back, chest and neck. Ultimately, the bones may fuse together, causing a limited range of motion of the spine and limiting one’s mobility.

Shoulders, hips and sometimes other joints may be involved.

AS may affect tendons and ligaments. For example, the heel may be involved with Achilles.

Tendonitis and plantar fasciitis.

Since it is a systemic disease, patients can get fever and fatigue, eye or bowel inflammation, and Rarely, there can be heart or lung involvement.

AS is typically non-life-threatening.

Usually, it is a slowly progressive disease. Most people are able to work and function normally.

How is ankylosing spondylitis (AS) diagnosed?

The diagnosis is typically suspected by the doctor based on the signs and symptoms. The doctor will take a thorough history and do a physical examination.

X-rays, especially those of the sacroiliac joints and spine, can be confirmatory.

If X-rays do not show enough changes, but the symptoms are highly suspicious, your doctor might order magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, which shows these joints better and can pick up early involvement before an X-ray scan.

The HLA B27 gene may be checked by a blood test, but its presence or absence does not ultimately confirm or reject the diagnosis.

How is ankylosing spondylitis (AS) treated?

Can psoriasis be cured?

At this time, there is no known curative treatment.

The goals of treatment are to reduce pain and stiffness, slow progression of the disease, prevent deformity, maintain posture and preserve function.

Exercise programs are an essential part of the treatment.

Patients may be referred for a formal physical therapy program. Patients with AS are given daily exercises for stretching and strengthening, deep breathing exercises and posture exercises to avoid stooping and slumping. Most recommended are exercises that promote spinal extension and mobility.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are traditionally used to control symptoms. There are many drug treatment options. The first lines of treatment are the NSAIDs, such as naproxen, ibuprofen, meloxicam or indomethacin. No one NSAID is superior to another. Given in the correct dose and duration, these drugs give great relief for most patients.

Steroids, such as cortisone or prednisone, are rarely used, except for with injections to a tendon or joint. Sometimes, medications that are normally used for rheumatoid arthritis, such as sulfasalazine or methotrexate, may be used. These appear to be less helpful for spine disease.

Frequent exercise is essential to maintain joint and heart health.

If you smoke, try to quit. Smoking aggravates spondyloarthritis and can speed up the rate of spinal fusion.

TNF alpha-blockers (a newer class of drugs known as biologics) are very effective in treating both the spinal and peripheral joint symptoms of spondyloarthritis. TNF alpha-blockers that the FDA has approved for use in patients with ankylosing spondylitis are:

infliximab (Remicade), which is given intravenously (by IV infusion) every 6-8 weeks at a dose of 5 mg/kg;

etanercept (Enbrel), given by an injection of 50 mg under the skin once weekly;

adalimumab (Humira), injected at a dose of 40 mg every other week under the skin;

Golimumab (Simponi), injected at a dose of 50 mg once a month under the skin.

However, anti-TNF treatment is expensive and not without side effects, including an increased risk for serious infection. Biologics can cause patients with latent tuberculosis (no symptoms) to develop an active infection.

Therefore, you and your doctor should weigh the benefits and risks when considering treatment with biologics. Those with arthritis in the knees, ankles, elbows, wrists, hands and feet should try DMARD therapy before anti-TNF treatment.

These drugs may not only help symptoms but also slow the progression of the disease. They are only given as IV’s in the doctor’s office or by self-administered shots at home.

Does surgery help?

Surgical options are limited. Total hip replacement is very useful for those with hip pain and disability due to joint destruction from cartilage loss. Spinal surgery is rarely necessary, except for those with traumatic fractures (broken bones due to injury) or to correct excess flexion deformities of the neck, where the patient cannot straighten the neck.

Broader health impacts

Other problems can occur in patients with spondyloarthritis.

Osteoporosis, which occurs in up to half of patients with ankylosing spondylitis, especially in those whose spine is fused. Osteoporosis can raise the risk of a spinal fracture.

Inflammation of part of the eye called uveitis, which occurs in about 40% of those with spondyloarthritis. Symptoms of uveitis include redness and pain in the eye. Steroid eye drops most often are effective, though severe cases may need other treatments from an ophthalmologist.

Inflammation of the aortic valve in the heart, which can occur over time in patients with spondylitis.

Psoriasis, a patchy skin disease, which, if severe will need treatment by a dermatologist

Intestinal inflammation, which may be so severe that it requires treatment by a gastroenterologist.

Psoriasis cannot be cured, but treatment greatly reduces symptoms, even in severe cases. Tips for improving psoriasis in addition to prescription medicines:

Use moisturizer.

Avoid using harsh soaps.

Apply oil or moisturizer after bathing.

Use tar or salicylic acid shampoo for scale on the scalp.

What is psoriatic arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of inflammatory arthritis.

Up to 30 per cent of people with psoriasis can develop psoriatic arthritis.

Both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are chronic autoimmune diseases – meaning conditions in which certain cells of the body attack other cells and tissues of the body.

Psoriasis is most commonly seen as raised red patches or skin lesions covered with a silvery white build-up of dead skin cells, called a scale.

Scales can occur on any part of the body. Psoriasis is not contagious – you cannot get psoriasis from being near someone with this condition or from touching psoriatic scales.

There are five different types of psoriatic arthritis. The types differ by the joints involved, ranging from only affecting the hands or spine areas to a severe deforming type called arthritis mutilans.

Like psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis symptoms flare and subside, vary from person to person, and even change locations in the same person over time.

How is psoriatic arthritis diagnosed?

There is no single test to diagnose psoriatic arthritis. Doctors make the diagnosis based on a patient’s medical history, physical exam, blood tests, laboratory tests and MRIs and/or Xrays of the affected joints.

X-rays are not usually helpful in making a diagnosis in the early stages of the disease.

In the later stages, X-rays may show changes that are more commonly seen only in psoriatic arthritis.

The diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis is easier for your doctor to confirm if psoriasis exists along with symptoms of arthritis.

However, in as many as 15% of patients, symptoms of psoriatic arthritis appear before symptoms of psoriasis.

Since the disease symptoms can vary from patient to patient, it is even more important to meet with your doctor when symptoms worsen, or new symptoms appear.

What are the symptoms of psoriatic arthritis?

The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis may be gradual and subtle in some patients; in others, they may be sudden and dramatic.

The most common symptoms – and you may not have all of these of psoriatic arthritis are:

Discomfort, stiffness, pain, throbbing, swelling, or tenderness in one or more joints

Reduced range of motion in joints

Joint stiffness and fatigue in the morning

Tenderness, pain, or swelling where tendons and ligaments attach to the bone (enthesitis); example: Achilles’Achilles’ tendonitis

Inflammation of the eye (such as iritis)

Silver or grey scaly spots on the scalp, elbows, knees, and/or the lower spine

Inflammation or stiffness in the lower back, wrists, knees or ankles

Swelling in the distal joints (small joints in the fingers and toes closest to the nail), giving these joints a sausage-like appearance

Pitting (small depressions) of the nails Detachment or lifting of fingernails or toenails

Other tests supportive for the diagnosis

Positive testing for elevated sedimentation rate (indicates the presence of inflammation)

Positive testing for elevated C reactive protein (indicates the presence of acute inflammation)

A negative test for rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP( performed to rule out rheumatoid arthritis)

Anaemia a state in which there is a decrease in haemoglobin

Juvenile Idiopathic

What is juvenile idiopathic arthritis?

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common type of arthritis that affects children. It used to be known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, but the name was recently changed to reflect the differences between childhood arthritis and adult forms of rheumatoid arthritis.

JIA is a chronic (long-lasting) disease that can affect joints in any part of the body. In this disease, the immune system mistakenly targets the synovium, the tissue that lines the inside of the joint. The synovium responds by making excess fluid (synovial fluid), which leads to swelling, pain and stiffness. The synovium and inflammation process can spread to the surrounding tissues, eventually damaging cartilage and bone. Other areas of the body, especially the eyes, also may be affected by inflammation. Without treatment, JIA can interfere with a child’s normal growth and development. There are several main subtypes of JIA, which are based on symptoms and the number of joints involved.

Systemic arthritis — Also called Still’s disease, this type occurs in about 10 to 20 per cent of children with JIA. A systemic illness is one that can affect the entire person or many-body systems. Systemic JIA usually causes a high fever and a rash, which most often appears on the trunk, arms and legs. It also can affect internal organs, such as the heart, liver, spleen and lymph nodes. This type of JIA affects boys and girls equally and rarely affects the eyes.

Oligoarthritis — This type of JIA affects fewer than five joints in the first six months of disease, most often the knee, ankle and wrist joints. It also can cause inflammation of the eye (often the iris, the coloured area of the eye), called uveitis, iridocyclitis or iritis. About half of all children with JIA have this type, and it is more common in girls than in boys. Many children will outgrow this type of arthritis by adulthood. In some children, it may spread to eventually involve more joints.

Polyarthritis — This type of JIA affects five or more joints in the first six months, often the same joints on each side of the body. Polyarthritis can also affect the neck and jaw joints as well as small joints, such as those in the hands and feet. It is more common in girls than in boys.

Psoriatic arthritis — This type of arthritis affects children who have arthritis with the rash of psoriasis. Children frequently have nail changes that look like pitting. Arthritis can precede the rash by many years or vice versa.

Enthesitis-related arthritis — This type of arthritis often affects the spine, hips and enthesis (attachment point of tendons to bones) and occurs mainly in boys older than eight years. The eyes are often affected by this type of arthritis. There is often a family history of arthritis of the back (spondylitis) in male relatives.

What are the symptoms of JIA?

Symptoms vary depending on the type of JIA and may include: Morning stiffness, Pain, swelling and tenderness in the joints Limping (younger children may not be able to perform motor activities that they recently learned.)

Fever, Rash, Weight loss

Fatigue or irritability

Eye redness, eye pain, and blurred vision

What causes JIA?

The exact cause of JIA is not known. However, researchers are studying several factors that may be involved, alone or in combination, in triggering the inflammatory reaction seen in JIA. These factors include genetics, infection, and environmental factors that influence the immune system. JIA, however, is not a hereditary disease like cystic fibrosis, for example.

How common is JIA?

JIA is the most common type of arthritis in children. It affects about 1 in 1,000 children, or about 300,000 children in the United States.

How is JIA diagnosed?

There are no tests that specifically diagnose JIA. Rather, JIA is a diagnosis of exclusion, which means the doctor works to rule out other causes of arthritis and other diseases as the cause of the symptoms. In making a diagnosis of JIA, the doctor usually begins with a complete medical history that includes a description of symptoms and a complete physical examination. Imaging techniques such as X-rays or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can sometimes show the condition of the joints. Laboratory tests on blood, urine, and/or joint fluid may be helpful in determining the type of arthritis. These include tests to determine the degree of inflammation, antinuclear antibody (ANA), and rheumatoid factor. These tests also can help rule out other diseases — such as an infection, bone disorder, or cancer — or an injury as the cause of your child’s symptoms.

How is JIA treated?

The goals of treatment are to relieve pain, reduce swelling, increase joint mobility and strength, and prevent joint damage and complications. Treatment generally includes medications and exercise. Medications used to treat JIA include:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) — These medicines provide pain relief and reduce swelling but do not affect the course or prognosis of JIA. Some are available over the counter, and others require a prescription. Examples include ibuprofen and naproxen. These medicines can cause nausea and stomach upset in some people and need to be taken with food.

Corticosteroids (steroids) — In patients with oligoarthritis or in patients with very painful/ swollen joints with other types of JIA, these medications are very effective when given as an injection (shot) into the affected joint. If a child is younger or if several joints are injected, sedation is often used. In patients with more severe widespread disease, these medications occasionally need to be given by mouth as a pill. These medicines, when given by mouth, are effective but can have serious side effects—including weakened bones —especially when used for long periods. Doctors generally try to avoid using steroids in children because they can interfere with a child’s normal growth.

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) — These medications work by changing, or modifying, the actual disease process in arthritis. The aim of DMARD therapy is to prevent bone and joint destruction by suppressing the immune system’s attack on the joints. Methotrexate (Rheumatrex®, Trexall®) is the DMARD most often used to treat JIA. Other medications used include sulfasalazine (Azulfidine®) and leflunomide (Arava®).

Biological modifying agents — Biological agents are medications that directly target molecules or proteins in the immune system that are responsible for causing inflammation. They are given by injection or by infusion and are used to treat children with more severe arthritis that is not responsive to other medications. Etanercept (Enbrel®), infliximab (Remicade®), adalimumab (Humira®), abatacept (Orencia®) and anakinra (Kineret®) are examples of this type of medication.

Exercise and physical and occupational therapy can help reduce pain, maintain muscle tone, improve mobility (ability to move) and prevent permanent handicaps. In some cases, splints or braces also may be used to help protect the joints as the child grows. Special accommodations with schools may be needed to adjust for children with limitations from their arthritis. The Americans with Disabilities Act (“504” plan) can help facilitate these issues.

What is the outlook for people with JIA?

JIA affects each child differently. For some, the disease is mild and easy to control, with only one or two joints affected. For others, JIA may involve many joints, and the symptoms may be more severe and may last longer. With the help of modern medical, physical, and occupational therapy, it is possible to achieve good control of arthritis, prevent joint damage, and enable the normal or near-normal function for most patients. Early detection and treatment may help to control inflammation, prevent joint damage, and maintain your child’s ability to function.

What complications are associated with JIA?

If it is untreated, JIA can lead to: Loss of vision or decreased vision due to iridocyclitis/uveitis

Permanent damage to joints

Chronic arthritis and disability (loss of function)

Interference with a child’s bones and growth

Inflammation of the membranes surrounding the heart (pericarditis) or lungs (pleuritis)

How the eye works

Although it might not seem possible, a disease that affects the joints can sometimes also affect the eyes. Children with juvenile idiopathic (formerly called rheumatoid) arthritis (JIA) can develop eye problems either as a result of the disease itself or, rarely, as a side effect of some medicines. This information will help you learn more about how JIA might affect your child’s eyes. The eye functions in the same way as the inner workings of a camera.

The front of the eye admits light rays through the cornea, the pupil (the middle of the iris that determines how much light enters the eye), and a transparent fluid known as the aqueous humour in the anterior chamber.

Next, the lens focuses that light through a clear gel-like substance called the vitreous humour onto the retina. The retina is a thin layer of tissue that makes up the inner lining of the back of the eye. The retina works like the film in a camera, transforming light into images. It converts the light rays to impulses that travel along the optic nerve to the brain. The brain integrates the images sent from both eyes and interprets them as a single, three-dimensional image, allowing us to perceive depth and distance.

If any of the parts of the eye become damaged, changes in eyesight can occur.

What are some common eye problems that might affect children with JIA?

Uveitis is the most common eye problem that can develop in children with JIA. Uveitis is an inflammation of the inner parts of the eye. The uvea consists of the iris (the coloured portion of the eye), the ciliary body (which produces fluid inside the eye and controls the movement of the lens) and the choroid (which lines the eyeball from the iris all the way around the eye).

Uveitis might also be known as iritis or iridocyclitis, depending on which part of the eye is affected by inflammation. If the inflammation is not detected and treated early, scarring and vision problems can occur. Glaucoma, cataracts, and permanent visual damage (including blindness) are all complications that could result from severe uveitis.

Uveitis can occur up to one year before, at the same time as, or up to 15 years after JIA is diagnosed. It can also occur several years after JIA is in remission (the disease is not active). The severity of the child’s joint disease does not determine how serious the uveitis might be. However, eye problems are more common in children with oligoarthritis (less than five joints with arthritis in the first six months of disease). Eye problems are also more likely if your child has a positive blood test for antinuclear antibodies (ANA). They are most likely to occur in female toddlers.

How will I know if my child is developing eye problems?

Because eye inflammation usually is not painful and the eyes are usually not red (“pink”), most children with JIA who develop eye problems do not have any symptoms. Rarely, children might complain of light bothering their eyes or blurred vision. Sometimes your child’s eyes might look red or cloudy. However, these symptoms usually develop so slowly that permanent eye damage can occur before any visual difficulties are noticed.

In order to detect eye problems and prevent them from causing damage, your rheumatologist will schedule frequent appointments with a pediatric ophthalmologist.

How can eye problems be prevented?

Carefully follow your health care provider’s medicine guidelines and keep all your scheduled appointments with your rheumatologist and ophthalmologist, even if you don’t think your child has eye problems or if the JIA is less active.

How often should my child have eye examinations?

The frequency of your child’s eye exams will depend on the type of JIA he or she has, how long your child has had arthritis, and what medicines have been prescribed to treat it. Because uveitis is more common in children with certain types of JIA, such as oligoarthritis, or in polyarthritis with a positive ANA, more frequent eye examinations (every three to four months) might be recommended. Children with polyarthritis (when ANA is negative) require an examination every six months, and patients with systemic JIA usually need an ophthalmologist examination every 12 months. Eye exams should continue after your child’s arthritis goes into remission. Ask your rheumatologist and ophthalmologist how often your child’s eye exams should be scheduled and follow their recommendations. If eye problems are detected, more frequent examinations will be necessary.

How can eye problems be treated?

If eye problems occur, your rheumatologist and ophthalmologist will discuss ways to treat them to prevent permanent eye damage. If uveitis is diagnosed, different types of eye drops might be prescribed. Eye drops to dilate the eyes may be prescribed in order to keep the pupils open and help prevent scarring. Steroid (cortisone) might be prescribed to reduce swelling and decrease inflammation. However, long-term use of steroid eye drops can have significant side effects such as glaucoma and cataracts.

If eye drops are not effective in decreasing inflammation, oral steroids (taken by mouth) might be prescribed. Oral or injectable methotrexate is now often used to treat significant eye inflammation, so the long-term side effects of steroids can be avoided. In cases of severe uveitis, new “biologic modifying medicines,” such as infliximab (Remicade®) or adalimumab (Humira®), may be used.

Osteoarthritis

What is Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent type of arthritis affecting millions of individuals It differentially affects older individuals over the age of 65 years. OA is a chronic degenerative arthropathy that frequently leads to chronic pain and disability.

Osteoarthritis: Epidemiology & Risk Factors

Epidemiology

OA is the most common type of arthritis.

Reported incidence and prevalence rates of OA in specific joints vary widely, due to differences in the case definition of OA. OA may be defined by radiographic criteria alone (radiographic OA), typical symptoms (symptomatic OA), or by both. Using radiographic criteria, the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the hand have been identified as the joints most commonly affected by OA, but they are the least likely to be symptomatic. In contrast, the knee and hip, which constitute the second and third most common locations of radiographic OA, respectively, are nearly always symptomatic. The first metatarsal phalangeal and carpometacarpal joints are also frequent sites of radiographic OA, while the shoulder, elbow, wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints rarely develop idiopathic OA.

Risk Factors for Osteoarthritis

AGE: In demographic studies, age is the most consistently identified risk factor for OA, regardless of the joint being studied. Prevalence rates for both radiographic OA and, to a lesser extent, symptomatic OA rise steeply after age 50 in men and age 40 in women. OA is rarely present in individuals less than 35 years of age, and secondary causes of OA or other types of arthritis should strongly be considered in this population.

SEX: Female gender is also a well-recognized risk factor for OA. Hand OA is particularly prevalent among women.

OBESITY: Cohort studies have demonstrated a clear association of obesity with the development of radiographic knee OA in women and a weaker association with hip OA.

JOINT STRESS: Occupation-related repetitive injury and physical trauma contribute to the development of secondary (non-idiopathic) OA, sometimes occurring in joints that are not affected by primary (idiopathic) OA, such as the metacarpophalangeal joints, wrists and ankles.

GENETICS: Twin studies have demonstrated an important role for genetics in the development of OA.. Genome-wide studies continue to evaluate for particular chromosomes, particularly those involved in bone or articular cartilage structure and metabolism, and associations of familial OA.

Osteoarthritis: Differential Diagnosis

If a patient has the typical symptoms and radiographic features described above, the diagnosis of OA is relative straightforward and is unlikely to be confused with other entities. However, in less straightforward cases, other diagnoses should be considered:

Periarticular structure derrangement: Periarticular pain that is not reproduced by passive motion or palpation of the joint should suggest an alternate etiology such as bursitis, tendonitis or periostitis.

Inflammatory arthritis: If the distribution of painful joints includes MCP, wrist, elbow, ankle or shoulder, OA is unlikely, unless there are specific risk factors (such as occupational, sports-related, history of injury). Prolonged stiffness (greater than one hour) should raise suspicion for an inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis. Marked warmth and erythema in a joint suggests a crystalline etiology.

Other inflammatory / systemic condition: Weight loss, fatigue, fever and loss of appetite suggest a systemic illness such as polymyalgia rheumatica, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus or sepsis or malignancy. Current treatment for OA is limited to control of symptoms. At this time, there are no pharmacological agents capable of retarding the progression of OA or preventing OA.

Pharmacological Therapy

Acetaminophin: Several studies have shown acetaminophen to be superior to placebo and equivalent to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) for the short-term management of OA pain. At present, acetaminophen (up to 4,000 mg/daily) is the recommended initial analgesic of choice for symptomatic OA.

Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents (NSAIDs): NSAIDs have been an important treatment for the symptoms of OA for a very long time. The mechanism by which NSAIDs exert their anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects is via inhibition of the prostaglandin-generating enzyme, cyclooxygenase (COX) . In addition to their inflammatory potential, prostaglandins also contribute to important homeostatic functions, such as maintenance of the gastric lining, renal blood flow, and platelet aggregation. Reduction of prostaglandin levels in these organs can result in the well-recognized side effects of traditional non-selective NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naprosyn, indomethacin) – that is, gastric ulceration, renal insufficiency, and prolonged bleeding time. The elderly are at higher risk for these side effects. Other risk factors for NSAID-induced GI bleed include prior peptic ulcer disease and concomitant steroid use. Potential renal toxicities of NSAIDs include azotemia, proteinura, and renal failure requiring hospitalization. Hematologic and cognitive abnormalities have also been reported with several NSAIDs. Therefore, in elderly patients, and those with a documented history of NSAID-induced ulcers, traditional non-selective NSAIDs should be used with caution, usually in lower dose and in conjunction with a proton pump inhibitor. Renal function should be monitored in the elderly. In addition, prophylactic treatment to reduce risk of gastrointestinal ulceration, perforation and bleeding is recommended in patients > 60 years of age with: prior history of peptic ulcer disease; anticipated duration of therapy of > 3 months; moderate to high dose of NSAIDs; and, concurrent corticosteroids. The development of selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors offers a strategy for the management of pain and inflammation that is likely to be less toxic to the GI tract.

COX-2 Inhibitors: Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors are a class of NSAIDs) that recently received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. These specific COX-2 inhibitors are effective for the pain and inflammation of OA. Their theoretical advantage, however, is that they will cause significantly less toxicity than conventional NSAIDs, particularly in the GI tract. NSAIDs exert their anti-inflammatory effect primarily by inhibiting an enzyme called cyclooxygenase (COX), also known as prostaglandin (PG) synthase. COX catalyzes the conversion of the substrate molecule, arachidonic acid, to prostanoids.

Other Oral Analgesic Agents: For patients who cannot tolerate NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors other analgesics alone or in combination may be apporrpriate. Tramadol, a non-NSAID/COX2 non-opioid pain medication, can be effective to manage pain symptoms alone or in combination with acetaminophen. Opioids should be a last resort for pain management, often in late-stage disease, given their many side effects including constipation, somnolence, and potential for abuse.

Topical Agents: Topical analgesic therapies include topical capsaicin and methyl salicylate creams. There is an FDA approved topical NSAID for the treatment of OA, diclofenac gel, which can be particularly useful for patients who are intolerant to the gastrointestinal side effects of NSAIDs.

Intraarticular Therapies: The judicious use of intra-articular glucocorticoid injections is appropriate for OA patients who cannot tolerate, or whose pain is not well controlled by, oral analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents. Periarticular injections may effectively treat bursitis or tendonitis that can accompany OA. The need for four or more intra-articular injections suggests the need for orthopedic intervention. Intraarticular injection of hyaluronate preparations has been demonstrated in several small clinical trials to reduce pain in OA of the knee. These injections are given in a series of 3 or 5 weekly injections (depending on the specific preparation) and may reduce pain for up to 6 months in some patients.

Non-pharmacological Management

Weight reduction in obese patients has been shown to significantly relieve pain, presumably by reducing biomechanical stress on weight bearing joints. Exercise has also been shown to be safe and beneficial in the management of OA. It has been suggested that joint loading and mobilization are essential for articular integrity. In addition, quadricep weakness, which develops early in OA, may contribute independently to progressive articular damage. Several studies in older adults with symptomatic knee OA have shown consistent improvements in physical performance, pain and self-reported disability after 3 months of aerobic or resistance exercise. Other studies have shown that resistive strengthening improves gait, strength and overall function. Low-impact activities, including water-resistive exercises or bicycle training, may enhance peripheral muscle tone and strength and cardiovascular endurance, without causing excessive force across, or injury, to joints. Studies of nursing home and community-dwelling elderly clearly demonstrate that one additional important benefit of exercise is a reduction in the number of falls.

Surgical Management

Patients in whom function and mobility remain compromised despite maximal medical therapy, and those in whom the joint is structurally unstable, should be considered for surgical intervention. Patients in whom pain has progressed to unacceptable levels-that is, pain at rest and/or nighttime pain-should also be considered as surgical candidates